I Heard A Fly Buzz

A disquisitional reading of a classic Dickinson verse form past Dr Oliver Tearle

Decease is a theme that looms large in the verse of Emily Dickinson (1830-86), and perhaps no more and so than in the historic poem of hers that begins 'I heard a Fly fizz – when I died'. This is not just a verse form about death: it'southward a poem most the event of decease, the moment of dying. Below is the verse form, and a cursory analysis of its language and meaning.

I heard a Wing buzz – when I died –

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air –

Betwixt the Heaves of Storm –

The Optics around – had wrung them dry –

And Breaths were gathering business firm

For that last Onset – when the Male monarch

Exist witnessed – in the Room –

I willed my Keepsakes – Signed away

What portion of me be

Assignable – and then information technology was

In that location interposed a Fly –

With Blue – uncertain – stumbling Buzz –

Between the light – and me –

And then the Windows failed – and then

I could non see to meet –

'I heard a Fly buzz – when I died': summary

In summary, 'I heard a Fly buzz – when I died' is a poem spoken by a expressionless person: annotation the by tense of 'died' in that first line. The speaker is already expressionless, and is telling us about what happened at her deathbed. (Nosotros say 'her' but the speaker could well be male – Dickinson often adopts a male voice in her poems, so the point remains moot.)

And dying, one of the most momentous events in anyone'south life (and certainly the last), is foregrounded in that opening line – though not as much as it could be. No, starting time nosotros have to heard about the fly that buzzed.

The opening line, 'I heard a Wing buzz – when I died', is the opposite of anticlimax (that anti-climax where i starts grandly and so fizzles out, such as in Alexander Pope'due south celebrated line from The Rape of the Lock: 'Dost sometimes counsel accept, and sometimes tea'): here, nosotros beginning with the modest – the literally small – and end with the momentous, 'died'.

Everything, we are told, was notwithstanding and silent effectually the speaker'south deathbed. Even the mourners attending her take stopped weeping: 'The Eyes around – had wrung them dry out', meaning 'their optics had wrung themselves dry' or 'they had wrung their eyes dry' with crying. Now'south non the fourth dimension for tears: just stillness and silence. Everyone, Dickinson'southward speaker tells us, seemed braced for the moment when the speaker of the poem would die, and the 'King' would be  'witnessed' in the room – presumably King Death, coming to take the speaker abroad.

'witnessed' in the room – presumably King Death, coming to take the speaker abroad.

The speaker had just signed her will doling out her 'Keepsakes' to her beneficiaries, and information technology was then, we are told, after her last will and testament had been signed, that the wing 'interposed' itself in the scene. 'With Blueish – uncertain – stumbling Buzz' uses Dickinson's trademark dashes to great upshot, conveying the sudden, darting style flies tin move around a room, especially around lite.

We may not have thought of such a motion as 'stumbling' (can flying insects stumble?) and then the presence of the word pulls united states of america up brusque, makes us stumble over Dickinson'south line.

'I heard a Fly fizz – when I died': analysis

This fly comes betwixt the speaker and 'the low-cal'. Has she seen the light? How should we interpret this? Is it simply the candle or lamp in the room lighting information technology (such as would attract a bluebottle to it), or is the 'lite' signalling the arrival of that 'Rex', Death? Has he come for her?

And why then do the Windows fail, and how should nosotros analyse that last line, 'I could not run into to run across'? Perhaps one inkling is offered past the style we talk, in the English language, of 'seers' and 'second sight': seers were oftentimes bullheaded in that they couldn't physically come across, but in another sense they saw further than anybody else considering they had the souvenir of foresight and prophecy (consider Tiresias from Oedipus Male monarch). 'Second sight', similarly, is a supposed grade of clairvoyance whereby the gifted person has admission to an invisible world – the globe beyond death, for instance.

Then the speaker could be saying (at the moment of expiry itself?) that she could no longer physically meet in society to find her way forrad into the next globe. Consider the more than everyday phrase, 'I tin can't practice right for doing wrong': Dickinson'due south last line might be analysed equally a cryptic variation on that expression.

Flies, of course, are associated with death and the dead: they feed on the dead. Still the presence of this fly remains puzzling. How should we analyse 'I heard a Fly buzz' in terms of its central image or object: the fly itself? Is this association betwixt death and flies feeding on corpses and feces all at that place is to information technology, or is it the deliberate juxtaposition of the very small (a common insect) and the very big (expiry itself) that Dickinson wants u.s.a. to think virtually? The question remains open.

Dickinson'south rhymes can oft seem haphazard: half-rhymes, off-rhymes, words that have only the vaguest sounds in common between them. Yet at that place is a delicate interplay of rhymes in 'I heard a Fly buzz'. 'Room' and 'Storm' in that first stanza are echoed in the following stanza, which has 'firm' and 'Room'; 'died' becomes tautened, or dried out, into 'dry'; in the third stanza, the 'be' that rhymes with 'Wing' calls upwards the 'Buzz' that is suggested by be(e), as well equally the rhyming 'me' and 'see' in that final stanza. ('Buzz' is also foreshadowed by 'was' in the preceding stanza, with this modest verb existence retrospectively encouraged to join in the onomatopoeia of 'Buzz'.)

In the last analysis, 'I heard a Fly buzz – when I died' is one of Emily Dickinson's most popular poems probably because of its elusiveness, and because – like many of her not bad poems, and her meditations on death – it raises more questions than information technology settles. How do you translate the fly in this poem?

About Emily Dickinson

Perhaps no other poet has attained such a high reputation after their death that was unknown to them during their lifetime. Born in 1830, Emily Dickinson lived her whole life within the few miles effectually her hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts. She never married, despite several romantic correspondences, and was better-known as a gardener than as a poet while she was alive.

Nevertheless, it's not quite true (as information technology'southward sometimes alleged) that none of Dickinson's poems was published during her own lifetime. A handful – fewer than a dozen of some i,800 poems she wrote in total – appeared in an 1864 anthology, Drum Shell, published to raise coin for Union soldiers fighting in the Civil War. But it was four years after her expiry, in 1890, that a volume of her poetry would appear earlier the American public for the offset time and her posthumous career would begin to take off.

Dickinson collected around eight hundred of her poems into little manuscript books which she lovingly put together without telling anyone. Her poetry is instantly recognisable for her idiosyncratic use of dashes in place of other forms of punctuation. She oftentimes uses the iv-line stanza (or quatrain), and, unusually for a nineteenth-century poet, utilises pararhyme or one-half-rhyme as often as total rhyme. The epitaph on Emily Dickinson'southward gravestone, composed past the poet herself, features only two words: 'chosen back'.

If y'all liked this verse form, you might too enjoy these ten curt poems virtually death, and Dickinson's classic poem about a snake, 'A narrow Beau in the Grass'. If you want to ain all of Dickinson's wonderful verse in a single book, yous tin can: we recommend the Faber edition of her Consummate Poems .

The author of this commodity, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English language at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others,The Hush-hush Library: A Book-Lovers' Journey Through Curiosities of History andThe Bang-up War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

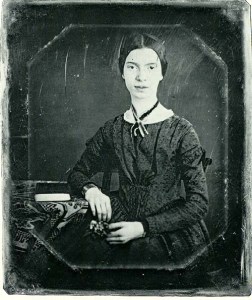

Image: Black/white photograph of Emily Dickinson by William C. Due north (1846/vii), Wikimedia Commons.

I Heard A Fly Buzz,

Source: https://interestingliterature.com/2016/09/a-short-analysis-of-emily-dickinsons-i-heard-a-fly-buzz-when-i-died/

Posted by: belcheremanded.blogspot.com

0 Response to "I Heard A Fly Buzz"

Post a Comment